Does God really exist ? It is a question many of us may wonder about at selected time in our lives. It is hard if not scientifically impossible to prove. However, now and then the Good Lord sends us signs, signs in the form of unexplainable things or in the form of something really good. God loves all human beings and during the past weekend God showed that he particularly loves jūdōka. To do so he took a human form and descended on this earth. The identity he took he called “Okano Isao”. For two days long God celebrated jūdō mass and while welcomed true believers of pure jūdō to feel His love.

On such solemn occasion I felt the Judo Forum needed to be represented, so I took the humble task upon me to be your ambassador and open myself up to His word and the Jūdō Gospel determined to bring its essence now to you in a simple and brief sermon of jūdō faith. I had to make a choice this year between attending the Kōdōkan International Summer Kata Course or Okano-sensei’s clinic. I chose the latter, and given some of the kata clips from Tōkyō which meanwhile have been posted on YouTube and in this very forum, I made the right choice. Let it be known that making this choice was not particularly hard. Okano-sensei, this time was a guest of Nakamura Hiroshi, 9th dan of Jūdō Canada and 8th dan Kōdōkan, himself a legend in Canada and respected among the jūdō elite for his successful training of Sydney Olympic silver medalist Nic Gill and many others. I did not miss the parade of geriatric red and white and more red which was so abundantly present on the Kōdōkan videos. Instead, everyone was wearing humble and discreet black belts, unless of course one was a kyū rank.

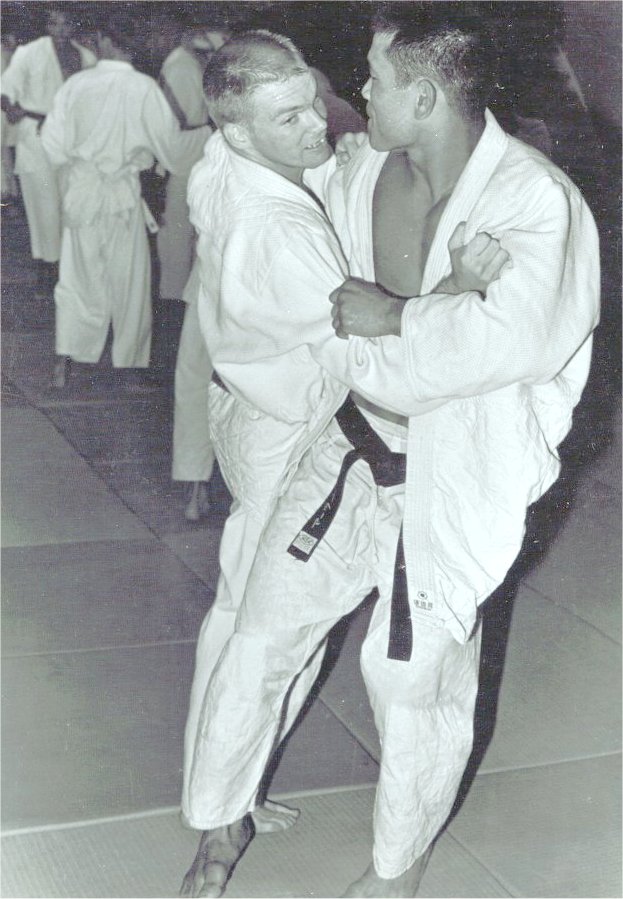

I believe it is entirely justified to not introduce Okano Isao here any further. If not, certainly my sermon would be anything but brief. One of most legendary jūdōka of all time, in a short list populated by the likes of Kimura and Mifune, and by many believed to be the greatest living jūdōka. Okano-sensei currently enjoying his retirement from his university, these days teaches jūdō clinics at the same frequency most of us meet a unicorn in our garden. Unlike the Kōdōkan’s department of geriatric jūdō, Okano is little interested in foregoing the essence of the martial art of jūdō and replacing it by a perverted superficial parody where your skills are judged by the angle your foot is in and your subsequent score in a kata contest a few days later. Instead, the man, if necessary, creates jūdō on the spot, true jūdō that is, true to its core. Needless to say that he demonstrates everything himself, and he does so flawlessly with the agility, speed and comfort of a jūdō wizard. Contrary to the Kōdōkan, Okano-sensei has the ability to teach in intelligible English, so no going on and on in Japanse while knowing that except for 2 or 3 people there no one understands a thing only to wait for a translator with the competency of someone who flunked out 2 weeks after the start of English 101. No such amateurism during Okano’s classes. Consequently, people feel respected and that feeling is also present in Okano’s teaching approach. He is patient and understands your level, and teaches without patronization.

I left my place of lodging almost 2 hours before the start of the clinic wanting to make sure I would arrive in time. That was a smart move, I think, since I got stuck in the subway for some time after the line temporarily closed down to remove a train that had broken down. This added at least 30-40 minutes to the normal travel time. I also couldn’t remember the exact subway station I had to get off and it turned out I made a mistake and chose one station to early. Thanks to the extra time I had reserved I was able to walk that extra distance and in the end arrived 10 minutes before the start of the clinic. Sharp timing, I would say.

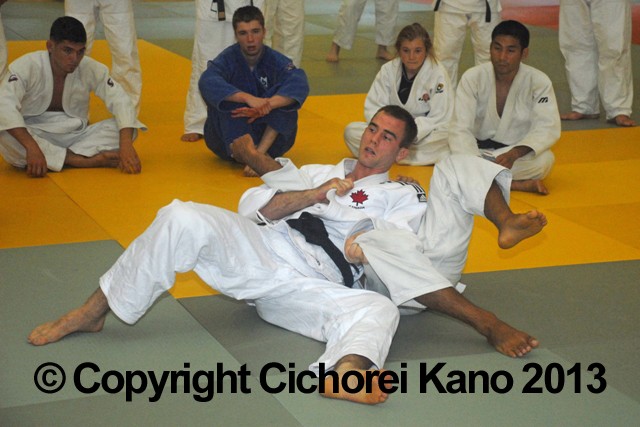

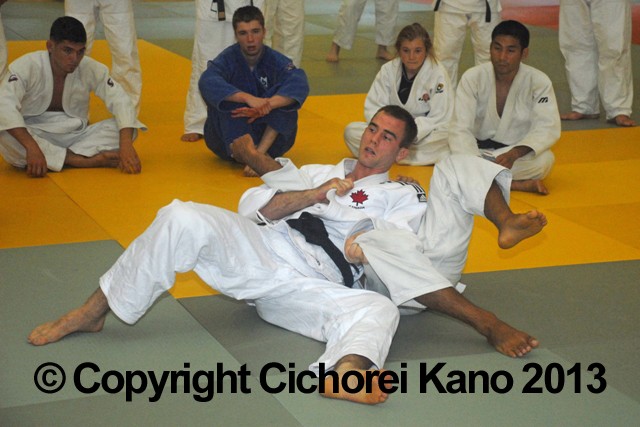

The clinic started with newaza, lots of newaza. Within seconds Okano was drawing ‘Ooohs’ and ‘waws’ from the mixture of common mortals and Olympic jūdō medal winners. Much of what Okano does, is not found in jūdō books authored by others, which in more simple terms means that it is his own creativity. His newaza is seamless. He shakes turnovers, defenses, escapes, katame-waza out of his sleeve, no, he shakes them out of both sleeves at the same time. You resist, you will soon regret it as he will turn you over the other side without even having to think what he needs to do. It is automatic, but not automatic in a sense of pre-programmed, more automatic in terms of instinctive expertise to create jūdō on the spot.

Despite my familiarity with Okano-sensei’s teaching, everytime he teaches there are some moves, some techniques, some turnovers, I have not seen before, and they are not always easy to remember. But Okano is patient and understands that we are not him. He understands that we do not just know and remember all these. So, his approach is more one of practicing all of them and choosing a couple and continue to practice those.

In addition to that, the techniques I was familiar with, I no doubt learnt more about this time just like I did the times before. Okano-sensei is like a gifted pianist who when he gives a recital makes you suddenly hear notes in the score you have never before realized they were there despite knowing the score through and through. So, details of importance, pointers, things that needed attention, were all emphasized, and by providing a rationale. This was teaching that was infused with Western pedagogical concepts, something rarely seen in Japanese-sensei, whose courses oftentimes in pedagogical terms are anything but brilliant.

The weather in good ol’ Montreal was decent and bearable, no Tōkyō summers of 95°F and 95% humidity, but a pleasant 78°F with a gentle breeze. So practice was well bearable although I must admit my knees were not used anymore to such lengthy newaza sessions. But that’s just some skin and soft tissue irritation, nothing more. Everyone, young and old, champs and mere mortals, diligently practiced. We knew we were there to learn, and we knew we were learning from the very best.

The last one third of the Friday evening’s session was devoted to Tachi-waza. This was a unique session. I don’t know if everybody picked up on it, but the session was valuable not just by the techniques he showed, but because he addressed some very fundamental issues in jūdō and also provided some insights into his legendary accomplishments. Instead of focusing on a specific technique, Okano-sensei rather focused on concepts.

One of the important things he said, was to develop the ability to fight in relaxed way. He said that during the All Japan Championships he had to fight people who weighed 130 kg, sometimes even up to 140 kg. If as a much lighter jūdōka you face those people with force, you’ll be drained soon, because they have far more force than you. Instead, you should fight in a relaxed way and accumulate your force during an attack. Thus learning to fight with relaxed arms while avoiding being thrown, is very important.

Secondly, he emphasized the importance of tai-sabaki and he described a large part of his successes to his mastership of tai-sabaki both in Tachi- and newaza. Therefore he recommended that judoka today should focus on that and develop these skills. He said that due to the IJF’s continuous changes today (he was clearly very critical of this) you can’t anymore compare jūdō. Nevertheless, the fundamentals of successful jūdō if at least jūdō, remain the same.

Everybody listened carefully and the things he said made much sense. He illustrated this with two techniques, seoi-nage (of which he did version that was closer to the Koga-version than to the spiraling form), and with a technique many of us probably consider too basic to even practice, i.e. ō-goshi. You could say that many black belts only that evening properly learnt ō-goshi, a throw typically on the program for 6th or 5th kyū.

Next Okano, sensei led us through some of his tokui-waza. This time he skipped ko-uchi-gari which he has frequently addressed in previous clinics. Now, his focus was on ō-soto-gari and seoi-nage in particular on how to combine these techniques or use them as counters, or simply in a competitive situation. From his explanations, it was obvious that he had done an enormous amount of analysis in his life, which, to be honest, is not surprising given his exceptional expertise and accomplishments. Okano-sensei emphasized several things that I have emphasized on this forum before. For example, he pointed out the frequent mistakes made in ō-soto-gari. It is something I have hammered on many times before too. He pointed to the frequent mistake of pulling uke’s arm across your chest while swinging out your leg high to the front. According to Okano-sensei this approach ‘can’ work, but only if you are either significantly taller or otherwise physically dominate your opponent, the same with some grips over the shoulder. This fits my own experiences. I have undergone the ō-soto-gari of -95 kg 1980 Olympic champion Robert Van De Walle and of his 1984 successor Ha Hyung-Jo from Korea. Both were very powerful players and both are half a head taller than me. It is obvious that the only reason they could do this is because they literally “overpower” me. I could never do the same to them.

As Okano-sensei pointed out, ō-soto-gari requires pulling with the hikite towards your left hip. In addition, a problem is often caused due to not being in at an ideal distance and being too far. According to Okano, one can avoid this problem by trying to get rid of coming in ō-soto-gari with the left, foot, and instead coming in with the right foot, thus making an extra step. In other words, the classical left foot step, should ideally be preceded by a forward right foot step. Okano himself oftentimes solves this by his unusual entry for ō-soto-gari, namely in tsuri-komi-movement, just like you would come in ko- or ō-soto-gari. He is the only jūdōka I know of who enters ō-soto-gari like this, although as he said the classical way is also OK as long as it is preceded by a right foot step.

Okano-sensei then illustrated and emphasized the above concept when using ō-soto-gari as a counter, and he did so too for seoi-nage, while integrating the proper steps in the whole framework of tai-sabaki.

Furthermore, he spent time addressing some of the crucial mistakes people tend to make in morote-seoi-nage. This too is something I have previously hammered on. Most people do not really perform morote-seoi-nage when they think they do; what they really are doing is ippon-seoi-nage with one arm folded and an elbow under the armpit. That, however, does not make it morote-seoi-nage, but that's another story. Anyhow, Okano-sensei emphasized that you are likely in problems and put your tsurite arm at risk for injury if you just obliquely put it in the armpit as many do. This is something in my teaching I overcome by properly pulling with both hands while entering vertically with the right arm rather than obliquely or horizontally. Okano-sensei uses an alternative approach to solve this problem. What he does is pulling vertically with the right arm. From there on the step are the same, but the vertical pulling is quite unique.

The clinic ended for that day at 8 pm, at which time a free barbecue was programmed. I must thank our Canadian friends again for their hospitality and kindness. I was able to listen to some very interesting conversations among Okano and the other Japanese sensei, which covered everything from the IJF to the Kōdōkan. Naturally, as these were conversations I overheard and which were in essence private I am not at liberty to disclose any of it, but let’s say that I learnt a lot.

When you do jūdō after having to travel, fatigue always kicks in a lot quicker and that was no different this time. Hence I did not wait until the very last person before heading back to my place of lodging.

We all were present again on Saturday 10 am sharp for the second day of jūdō wisdom. Once more the majority of material was devoted to newaza, mostly nogare-kata and hairi-kata (turnovers and entries) in a systematic way, that is to say, one technique applicable from many angles and situations. In other words, it was a true newaza clinic rather than a katame-waza clinic.

When Okano-sensei concluded his teaching at 12 noon, we all felt we had learnt a great deal that would still take months to process and work on in our local clubs. We were grateful to have been given this chance to learn from the best under the best, and awarded Okano-sensei and his host Nakamura-sensei with a warm and loud applause.

There was a noon session of randori from 12-1pm giving you an opportunity to uchi-komi and randori with former and current Canadian champions. Two of these, namely Sydney Olympian Nicolas Gill (silver medalist upon losing in the famous uchi-mata by Inoue Kosei in the -100 kg) and Antoine Valois-Fortier (London 2012 bronze medalist in -81 kg, a boyish-looking very tall jūdōka, taller than me and I’m 6’0”). Both jūdōka presented their newaza tokui-waza skills, thus again mostly nogare-kata (turnovers) and hair-kata (entries).

Our Forum colleague Ben Reinhardt had previously elaborated on his positive experiences while attending a clinic by Valois-Fortier who to me was previously largely unknown. Having now met the man, I must concur. Despite his relative youth and success, he was pretty down to earth, and equally patient hence together with the more experienced Gill succeeding in maintaining a pleasant learning environment. This would be the last practical session of the clinic.

In the meantime I also had been given an opportunity to be introduced at some of our Canadian JudoForum friends, who were sympathetic and kind to me. It is a privilege when we are given a time and opportunity to enjoy being brought together through jūdō irrespective of politics which these days do so much harm to our beloved discipline.

The evening would be concluded with a large banquet. There was an astronaut-member of parliament, the Japanese consul-general, the president of Chūō University, and many other notables, while the USA Judo/USJF was represented by Saito Noboru, all there to join into celebrating the 40th anniversary of Nakamura Hiroshi’s jūdō club.

I enjoyed salmon and other delicacies as well as some intelligent conversations with other expatriates, and some very erudite colleagues. Again I was not able to stay until the very last as I wasn’t sure how late the subway system would work. In times of economic crisis my travel too is impacted, so gone are the decent hotels, only to be replaced by lodging opportunities of modesty. You’d think I would have reason enough to complain about these conditions but you are wrong. Let it suffice to allude to the fact that my dormitory was mixed and that the three Bask girls in between whom I was spending the night a priori made up for anything a man could possibly complain about. I love jūdō clinics, especially the unexpected unplanned part of them !

On such solemn occasion I felt the Judo Forum needed to be represented, so I took the humble task upon me to be your ambassador and open myself up to His word and the Jūdō Gospel determined to bring its essence now to you in a simple and brief sermon of jūdō faith. I had to make a choice this year between attending the Kōdōkan International Summer Kata Course or Okano-sensei’s clinic. I chose the latter, and given some of the kata clips from Tōkyō which meanwhile have been posted on YouTube and in this very forum, I made the right choice. Let it be known that making this choice was not particularly hard. Okano-sensei, this time was a guest of Nakamura Hiroshi, 9th dan of Jūdō Canada and 8th dan Kōdōkan, himself a legend in Canada and respected among the jūdō elite for his successful training of Sydney Olympic silver medalist Nic Gill and many others. I did not miss the parade of geriatric red and white and more red which was so abundantly present on the Kōdōkan videos. Instead, everyone was wearing humble and discreet black belts, unless of course one was a kyū rank.

I believe it is entirely justified to not introduce Okano Isao here any further. If not, certainly my sermon would be anything but brief. One of most legendary jūdōka of all time, in a short list populated by the likes of Kimura and Mifune, and by many believed to be the greatest living jūdōka. Okano-sensei currently enjoying his retirement from his university, these days teaches jūdō clinics at the same frequency most of us meet a unicorn in our garden. Unlike the Kōdōkan’s department of geriatric jūdō, Okano is little interested in foregoing the essence of the martial art of jūdō and replacing it by a perverted superficial parody where your skills are judged by the angle your foot is in and your subsequent score in a kata contest a few days later. Instead, the man, if necessary, creates jūdō on the spot, true jūdō that is, true to its core. Needless to say that he demonstrates everything himself, and he does so flawlessly with the agility, speed and comfort of a jūdō wizard. Contrary to the Kōdōkan, Okano-sensei has the ability to teach in intelligible English, so no going on and on in Japanse while knowing that except for 2 or 3 people there no one understands a thing only to wait for a translator with the competency of someone who flunked out 2 weeks after the start of English 101. No such amateurism during Okano’s classes. Consequently, people feel respected and that feeling is also present in Okano’s teaching approach. He is patient and understands your level, and teaches without patronization.

I left my place of lodging almost 2 hours before the start of the clinic wanting to make sure I would arrive in time. That was a smart move, I think, since I got stuck in the subway for some time after the line temporarily closed down to remove a train that had broken down. This added at least 30-40 minutes to the normal travel time. I also couldn’t remember the exact subway station I had to get off and it turned out I made a mistake and chose one station to early. Thanks to the extra time I had reserved I was able to walk that extra distance and in the end arrived 10 minutes before the start of the clinic. Sharp timing, I would say.

The clinic started with newaza, lots of newaza. Within seconds Okano was drawing ‘Ooohs’ and ‘waws’ from the mixture of common mortals and Olympic jūdō medal winners. Much of what Okano does, is not found in jūdō books authored by others, which in more simple terms means that it is his own creativity. His newaza is seamless. He shakes turnovers, defenses, escapes, katame-waza out of his sleeve, no, he shakes them out of both sleeves at the same time. You resist, you will soon regret it as he will turn you over the other side without even having to think what he needs to do. It is automatic, but not automatic in a sense of pre-programmed, more automatic in terms of instinctive expertise to create jūdō on the spot.

Despite my familiarity with Okano-sensei’s teaching, everytime he teaches there are some moves, some techniques, some turnovers, I have not seen before, and they are not always easy to remember. But Okano is patient and understands that we are not him. He understands that we do not just know and remember all these. So, his approach is more one of practicing all of them and choosing a couple and continue to practice those.

In addition to that, the techniques I was familiar with, I no doubt learnt more about this time just like I did the times before. Okano-sensei is like a gifted pianist who when he gives a recital makes you suddenly hear notes in the score you have never before realized they were there despite knowing the score through and through. So, details of importance, pointers, things that needed attention, were all emphasized, and by providing a rationale. This was teaching that was infused with Western pedagogical concepts, something rarely seen in Japanese-sensei, whose courses oftentimes in pedagogical terms are anything but brilliant.

The weather in good ol’ Montreal was decent and bearable, no Tōkyō summers of 95°F and 95% humidity, but a pleasant 78°F with a gentle breeze. So practice was well bearable although I must admit my knees were not used anymore to such lengthy newaza sessions. But that’s just some skin and soft tissue irritation, nothing more. Everyone, young and old, champs and mere mortals, diligently practiced. We knew we were there to learn, and we knew we were learning from the very best.

The last one third of the Friday evening’s session was devoted to Tachi-waza. This was a unique session. I don’t know if everybody picked up on it, but the session was valuable not just by the techniques he showed, but because he addressed some very fundamental issues in jūdō and also provided some insights into his legendary accomplishments. Instead of focusing on a specific technique, Okano-sensei rather focused on concepts.

One of the important things he said, was to develop the ability to fight in relaxed way. He said that during the All Japan Championships he had to fight people who weighed 130 kg, sometimes even up to 140 kg. If as a much lighter jūdōka you face those people with force, you’ll be drained soon, because they have far more force than you. Instead, you should fight in a relaxed way and accumulate your force during an attack. Thus learning to fight with relaxed arms while avoiding being thrown, is very important.

Secondly, he emphasized the importance of tai-sabaki and he described a large part of his successes to his mastership of tai-sabaki both in Tachi- and newaza. Therefore he recommended that judoka today should focus on that and develop these skills. He said that due to the IJF’s continuous changes today (he was clearly very critical of this) you can’t anymore compare jūdō. Nevertheless, the fundamentals of successful jūdō if at least jūdō, remain the same.

Everybody listened carefully and the things he said made much sense. He illustrated this with two techniques, seoi-nage (of which he did version that was closer to the Koga-version than to the spiraling form), and with a technique many of us probably consider too basic to even practice, i.e. ō-goshi. You could say that many black belts only that evening properly learnt ō-goshi, a throw typically on the program for 6th or 5th kyū.

Next Okano, sensei led us through some of his tokui-waza. This time he skipped ko-uchi-gari which he has frequently addressed in previous clinics. Now, his focus was on ō-soto-gari and seoi-nage in particular on how to combine these techniques or use them as counters, or simply in a competitive situation. From his explanations, it was obvious that he had done an enormous amount of analysis in his life, which, to be honest, is not surprising given his exceptional expertise and accomplishments. Okano-sensei emphasized several things that I have emphasized on this forum before. For example, he pointed out the frequent mistakes made in ō-soto-gari. It is something I have hammered on many times before too. He pointed to the frequent mistake of pulling uke’s arm across your chest while swinging out your leg high to the front. According to Okano-sensei this approach ‘can’ work, but only if you are either significantly taller or otherwise physically dominate your opponent, the same with some grips over the shoulder. This fits my own experiences. I have undergone the ō-soto-gari of -95 kg 1980 Olympic champion Robert Van De Walle and of his 1984 successor Ha Hyung-Jo from Korea. Both were very powerful players and both are half a head taller than me. It is obvious that the only reason they could do this is because they literally “overpower” me. I could never do the same to them.

As Okano-sensei pointed out, ō-soto-gari requires pulling with the hikite towards your left hip. In addition, a problem is often caused due to not being in at an ideal distance and being too far. According to Okano, one can avoid this problem by trying to get rid of coming in ō-soto-gari with the left, foot, and instead coming in with the right foot, thus making an extra step. In other words, the classical left foot step, should ideally be preceded by a forward right foot step. Okano himself oftentimes solves this by his unusual entry for ō-soto-gari, namely in tsuri-komi-movement, just like you would come in ko- or ō-soto-gari. He is the only jūdōka I know of who enters ō-soto-gari like this, although as he said the classical way is also OK as long as it is preceded by a right foot step.

Okano-sensei then illustrated and emphasized the above concept when using ō-soto-gari as a counter, and he did so too for seoi-nage, while integrating the proper steps in the whole framework of tai-sabaki.

Furthermore, he spent time addressing some of the crucial mistakes people tend to make in morote-seoi-nage. This too is something I have previously hammered on. Most people do not really perform morote-seoi-nage when they think they do; what they really are doing is ippon-seoi-nage with one arm folded and an elbow under the armpit. That, however, does not make it morote-seoi-nage, but that's another story. Anyhow, Okano-sensei emphasized that you are likely in problems and put your tsurite arm at risk for injury if you just obliquely put it in the armpit as many do. This is something in my teaching I overcome by properly pulling with both hands while entering vertically with the right arm rather than obliquely or horizontally. Okano-sensei uses an alternative approach to solve this problem. What he does is pulling vertically with the right arm. From there on the step are the same, but the vertical pulling is quite unique.

The clinic ended for that day at 8 pm, at which time a free barbecue was programmed. I must thank our Canadian friends again for their hospitality and kindness. I was able to listen to some very interesting conversations among Okano and the other Japanese sensei, which covered everything from the IJF to the Kōdōkan. Naturally, as these were conversations I overheard and which were in essence private I am not at liberty to disclose any of it, but let’s say that I learnt a lot.

When you do jūdō after having to travel, fatigue always kicks in a lot quicker and that was no different this time. Hence I did not wait until the very last person before heading back to my place of lodging.

We all were present again on Saturday 10 am sharp for the second day of jūdō wisdom. Once more the majority of material was devoted to newaza, mostly nogare-kata and hairi-kata (turnovers and entries) in a systematic way, that is to say, one technique applicable from many angles and situations. In other words, it was a true newaza clinic rather than a katame-waza clinic.

When Okano-sensei concluded his teaching at 12 noon, we all felt we had learnt a great deal that would still take months to process and work on in our local clubs. We were grateful to have been given this chance to learn from the best under the best, and awarded Okano-sensei and his host Nakamura-sensei with a warm and loud applause.

There was a noon session of randori from 12-1pm giving you an opportunity to uchi-komi and randori with former and current Canadian champions. Two of these, namely Sydney Olympian Nicolas Gill (silver medalist upon losing in the famous uchi-mata by Inoue Kosei in the -100 kg) and Antoine Valois-Fortier (London 2012 bronze medalist in -81 kg, a boyish-looking very tall jūdōka, taller than me and I’m 6’0”). Both jūdōka presented their newaza tokui-waza skills, thus again mostly nogare-kata (turnovers) and hair-kata (entries).

Our Forum colleague Ben Reinhardt had previously elaborated on his positive experiences while attending a clinic by Valois-Fortier who to me was previously largely unknown. Having now met the man, I must concur. Despite his relative youth and success, he was pretty down to earth, and equally patient hence together with the more experienced Gill succeeding in maintaining a pleasant learning environment. This would be the last practical session of the clinic.

In the meantime I also had been given an opportunity to be introduced at some of our Canadian JudoForum friends, who were sympathetic and kind to me. It is a privilege when we are given a time and opportunity to enjoy being brought together through jūdō irrespective of politics which these days do so much harm to our beloved discipline.

The evening would be concluded with a large banquet. There was an astronaut-member of parliament, the Japanese consul-general, the president of Chūō University, and many other notables, while the USA Judo/USJF was represented by Saito Noboru, all there to join into celebrating the 40th anniversary of Nakamura Hiroshi’s jūdō club.

I enjoyed salmon and other delicacies as well as some intelligent conversations with other expatriates, and some very erudite colleagues. Again I was not able to stay until the very last as I wasn’t sure how late the subway system would work. In times of economic crisis my travel too is impacted, so gone are the decent hotels, only to be replaced by lodging opportunities of modesty. You’d think I would have reason enough to complain about these conditions but you are wrong. Let it suffice to allude to the fact that my dormitory was mixed and that the three Bask girls in between whom I was spending the night a priori made up for anything a man could possibly complain about. I love jūdō clinics, especially the unexpected unplanned part of them !